Yesterday, today and the future of scuba diving

The history of scuba diving – much less the history of all diving in general – could fill volumes. It’s an endeavor marked by the contributions of literally hundreds of individuals, some household names recognized by non-divers and others forgotten even by the most hardcore dive historians. But, all made the sport of scuba diving what it is today.

Scuba diving is a young activity – not even a century old if you go back to its earliest vestiges. It’s only 40 or so years old if you go back to when recreational scuba diving began largely as we practice it today. At this writing, quite a few of diving’s earliest contributors and pioneers are still with us.

However, they hint at possibilities to come: With innovations in materials lighter and more compact versions could be feasible. There’s little doubt there would be reasonable demand for a hard suit that’s not prohibitively expensive, rated to 100 metres (330 feet) for two or three hours, and simple and light enough for a single person to operate with little or no surface support. Will it happen? Perhaps sooner than you imagine.

There are probably hundreds of perspectives on the scuba diving timeline. For this very brief treatment, we’ll trace diving through five rough time blocks, following it from its inception as an obscure activity that relied primarily on homemade gear to a mainstream sport enjoyed by millions of people daily.

The Eclectic Calling of scuba diving: 1930’s and 1940’s

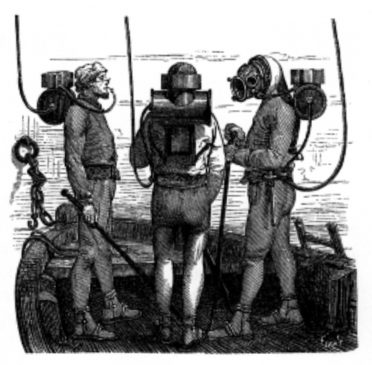

Scuba diving’s roots begin with a rare breed of adventurer who explored the underwater world more than a decade before the invention of the open-circuit scuba regulator. Although hard hat commercial and military diving had established themselves firmly by the 1930s, these divers (almost exclusively male) forayed underwater with snorkels fashioned from garden hoses and handcrafted spears, notably along the French Mediterranean coast and in southern California, USA. Almost the only commercially available equipment at the time was crude goggles and Corlieu fins. However, even these were hard to come by, so many early sport divers made due with homemade goggles and old-fashioned arm power for swimming. The primary motivator for these early explorers was underwater hunting.

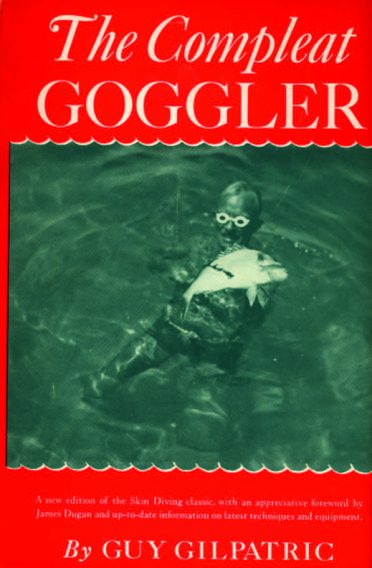

Perhaps the best-remembered pioneer from this era was Guy Gilpatric, an American journalist who explored the French Mediterranean. Gilpatric wrote what may be the first sport diver manual of any kind – The Compleat Goggler. Gilpatric introduced several people to his new sport, both personally and through his book. Among these was an ambitious young man named Jacques Cousteau.

Perhaps the best-remembered pioneer from this era was Guy Gilpatric, an American journalist who explored the French Mediterranean. Gilpatric wrote what may be the first sport diver manual of any kind – The Compleat Goggler. Gilpatric introduced several people to his new sport, both personally and through his book. Among these was an ambitious young man named Jacques Cousteau.

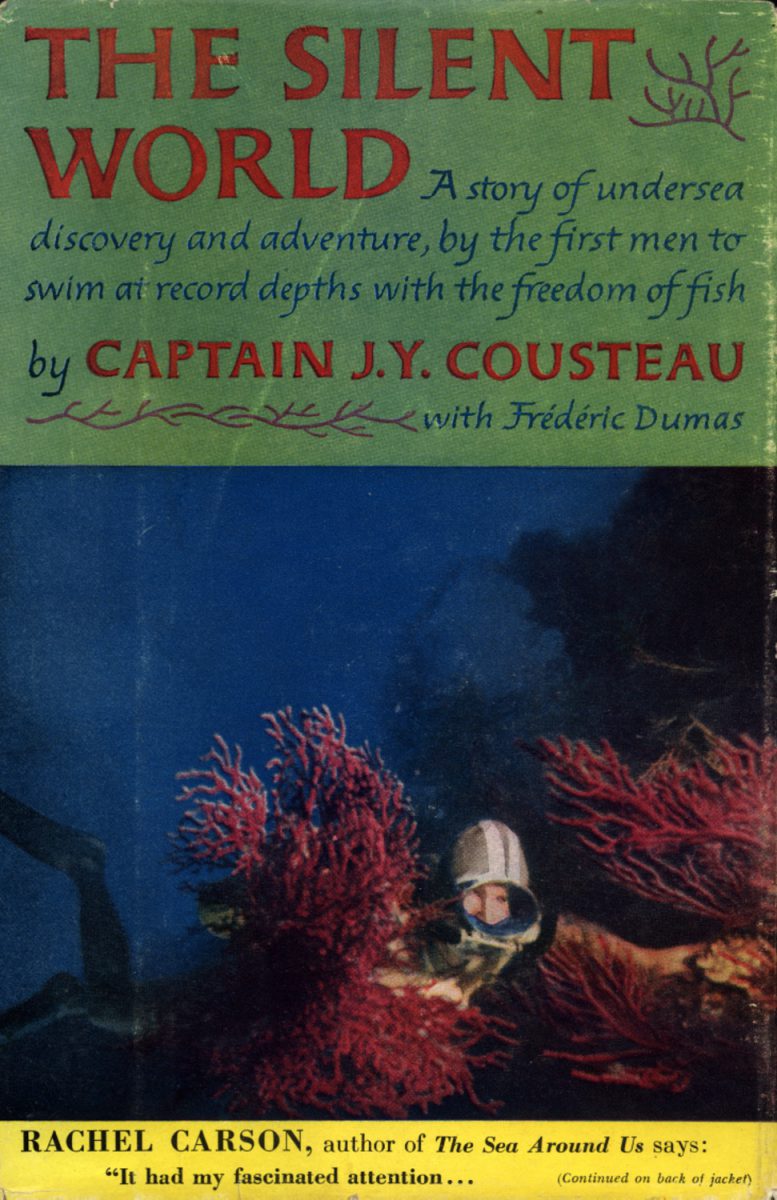

Cousteau recounts his early years in scuba diving in his classic, The Silent World. Cousteau explains that he began diving as a hunter. In the 1930s, he and his close companions Frederic Dumas, Philippe Tailliez and others, speared fish – some weighing more than 120 kg/280 lbs. Unlike some of these early explorers, however, their purpose for diving began to stray from hunting. They found themselves drawn to the sea’s mysteries and decided to explore the last frontier on earth.

Quickly reaching the practical time and depth limits of breath-hold diving, Cousteau wanted an air supply, but not clunky hardhat gear. In The Silent World he observed, “We wanted breathing equipment, not so much to go deeper, but to stay longer, simply to live awhile in a new world.”

Quickly reaching the practical time and depth limits of breath-hold diving, Cousteau wanted an air supply, but not clunky hardhat gear. In The Silent World he observed, “We wanted breathing equipment, not so much to go deeper, but to stay longer, simply to live awhile in a new world.”

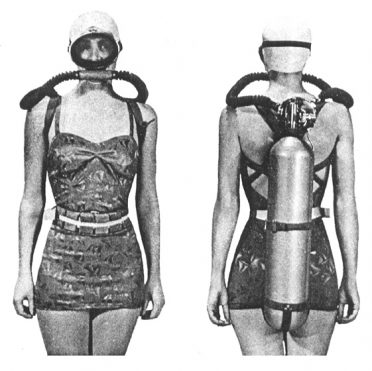

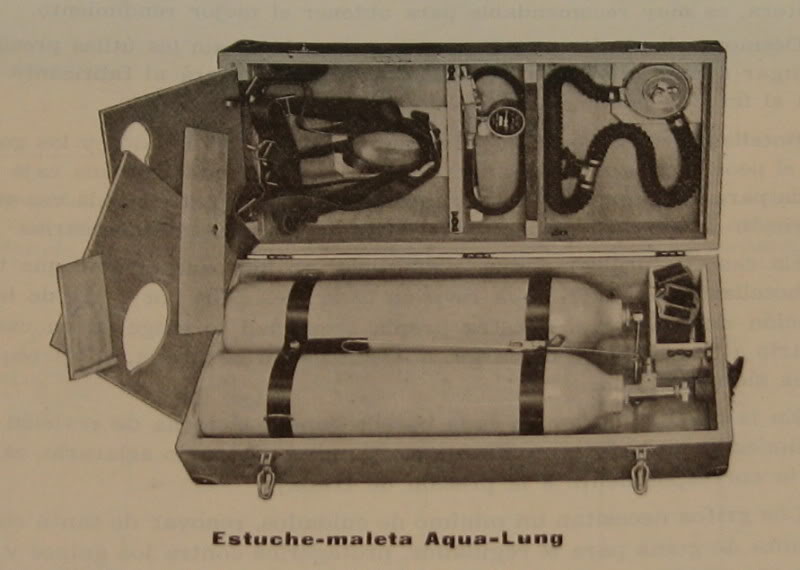

They experimented with the early pure oxygen rebreathers in use by military divers. While some early sport divers got good use from these, Cousteau and his companions quickly rejected it. The shallow depths imposed by breathing pure oxygen did little to expand their capabilities. They played with the “Le Prieur” compressed air device, but it proved impractical because its continuous air flow drained cylinders too rapidly. What they needed, Cousteau determined, did not exist. In 1942, Cousteau brought Emile Gagnan into the picture. Gagnan wasn’t a scuba diver, but a compressed gas engineer. Cousteau asked Gagnan to design a compressed air device that would deliver air at the surrounding water pressure only when the diver inhales. Gagnan did so, and after a few test devices and minor modifications, he and Cousteau patented the world’s first open-circuit scuba regulator, the Aqua-Lung. They probably had little idea what a breakthrough their invention would prove to be.

The Aqua-Lung changed everything for Cousteau and his friends. With the ability to stay underwater, their focus shifted from hunting to a new passion – underwater movies and photographs. In the late 1940s, they found a war-weary public hungry for movies, photos and stories about their underwater exploits. By 1950, Cousteau’s movies were popular in Europe and the United States. The public perception was that scuba diving was something you watch a few, select, highly motivated individuals do. But, the first shipments of Aqua-Lungs were starting to sell to an adventurous few who wanted to do more than watch this new calling. They wanted to do it.

The Aqua-Lung changed everything for Cousteau and his friends. With the ability to stay underwater, their focus shifted from hunting to a new passion – underwater movies and photographs. In the late 1940s, they found a war-weary public hungry for movies, photos and stories about their underwater exploits. By 1950, Cousteau’s movies were popular in Europe and the United States. The public perception was that scuba diving was something you watch a few, select, highly motivated individuals do. But, the first shipments of Aqua-Lungs were starting to sell to an adventurous few who wanted to do more than watch this new calling. They wanted to do it.

Scuba Diving Emerges: 1950’s and Early 1960’s

Most dive historians would say that scuba diving, much as we know it today, began about 1950. Fueled by books, films and photos about the underwater world, scuba diving began to grow. The first dive stores opened, and Aqua Lung quickly found itself competing with other fledgling manufacturers making their own versions of open-circuit regulators and other gear.

The equipment at the time was still primitive compared to today. In the early 1950s, only double hose regulators existed, with the buoyancy control device, submersible pressure gauge, alternate air source and other equipment we take for granted still more than a decade away. Even wetsuits didn’t exist on a broad scale until about the mid-1950s, with divers using crude, primarily handcrafted rubber dry suits that often didn’t keep you that dry. Without BCDs, your buoyancy changed throughout the dive as your wetsuit (if you had one) compressed and you consumed your air. If you were negatively buoyant and wanted to ascend, your only options were to swim up or to drop your weights.

But, equipment advancements came rapidly, so that by the mid-1960s, most divers were using single hose regulators, wet suits and other commercially made gear. The first SPGs had come out, but were not widely used yet, and the modern BCD was still five years away.

Scuba diver training was in its infancy. Most scuba diving instructors at the time were simply experienced divers – many formerly in the military – willing to share their passion with others. Unacquainted with mainstream education, most of these early instructors based their diving courses on the military’s, with an emphasis on weeding out those who didn’t measure up physically or mentally. A typical scuba diving course in that era involved extensive physical training, drills that had no real application in diving, and often weeks of underwater practice in a pool, but ironically no training in an actual open water diving environment. The first texts, like The Science of Skin and Scuba Diving (1957) taught facets of physics, physiology and other topics well beyond what you need to know to dive safely. Given the crude equipment and relative newness of the sport at the time, in many ways such a training model was arguably appropriate.

Despite the lack of sophistication, diver training hit some important milestones. Recognizing that training is needed to manage the risks of scuba diving, the young dive community developed the first certifications. These began as store-issued credentials, but with divers traveling to pursue their sport, the need for broad recognition rose quickly. Los Angeles County, NAUI (National Association of Underwater Instructors) and the YMCA Scuba Program emerged as the first national (US) and then international credentials.

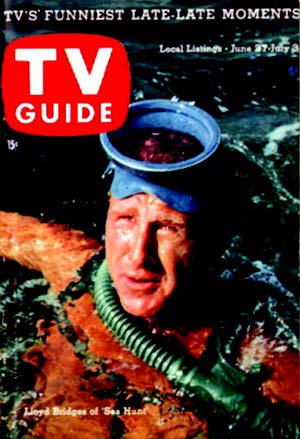

The public perception of scuba diving began to change during the era. Rather than viewed as an activity for an elite few, the public began to see scuba diving as something open to anyone who really wants to do it. In the United States, the main influence for this was Sea Hunt, a landmark television show starring Lloyd Bridges. In the role of diver Mike Nelson, Bridges portrayed underwater exploits for a half hour each week, giving much of the public its first glimpses of diving. One of the most successful syndicated shows in television history, Sea Hunt ran with more than 200 episodes that continued to play in rerun well into the 1960s. Even today, you can get episode collections on DVD. Sea Hunt inspired literally thousands of people to take up diving, and many leaders of today’s dive community will tell you that it all began for them as children watching this show.

Scuba Diving’s Adolescence. Mid 1960s through Mid-1970s

The mid 1960s through mid-1970s were transitional years for the sport-like scuba diving. This period saw the advancement and acceptance of key equipment. The BCD, for example, came into use in the form of inflatable horse collar vests that could be inflated orally (through a thin tube) or with a CO2 cartridge. Although awkward to use, many scuba divers (especially cave divers) noted the advantages of underwater buoyancy control. The French Fenzy BCD was the first vest with a large diameter inflation hose and attached air cylinder, and quickly led to almost every manufacturer offering similar BCDs with inflation from the scuba regulator. For the first time, scuba divers could maintain neutral buoyancy throughout a dive at the touch of a button, greatly reducing the overall physical exertion. By doing this, the low-pressure inflated BCD opened scuba diving to a much wider part of the public.

The mid 1960s through mid-1970s were transitional years for the sport-like scuba diving. This period saw the advancement and acceptance of key equipment. The BCD, for example, came into use in the form of inflatable horse collar vests that could be inflated orally (through a thin tube) or with a CO2 cartridge. Although awkward to use, many scuba divers (especially cave divers) noted the advantages of underwater buoyancy control. The French Fenzy BCD was the first vest with a large diameter inflation hose and attached air cylinder, and quickly led to almost every manufacturer offering similar BCDs with inflation from the scuba regulator. For the first time, scuba divers could maintain neutral buoyancy throughout a dive at the touch of a button, greatly reducing the overall physical exertion. By doing this, the low-pressure inflated BCD opened scuba diving to a much wider part of the public.

During this same period, the alternate air source (extra second stage), emerged from the young cave diving community. Generally credited to cave diver Hal Watts, who’s said to have simply tapped a new port into a first stage and screwed in another hose with a second stage, it would be more than a decade before it would be considered standard equipment for all scuba divers.

This period also gave rise to the decompression meter, a mechanical forerunner to the modern dive computer. Although available as early as 1959, it wasn’t until this era that it found widespread use, though most divers still used tables. The SPG, formerly seen as an optional instrument, was adopted as standard gear, along with the depth gage, watch/bottom time and compass. The first modern (variable volume) dry suits also came out, making it possible to dive with reasonable comfort in cooler water than ever before.

Despite these equipment advances, the public perception of scuba diving changed little. Most people saw scuba diving as something open to the daring, hardy few sportsmen (men still predominated) willing to accept risky adventures and peril. One reason for this was that diver training had not kept up with technology. Equipment advancements were making scuba diving viable for the broader public, but training still emphasized physical qualifications and weeding out. Although the double hose regulator was gone, many of the techniques taught – like buddy breathing to share air with a single mouthpiece – were still based on double hosed regulators.

Despite these equipment advances, the public perception of scuba diving changed little. Most people saw scuba diving as something open to the daring, hardy few sportsmen (men still predominated) willing to accept risky adventures and peril. One reason for this was that diver training had not kept up with technology. Equipment advancements were making scuba diving viable for the broader public, but training still emphasized physical qualifications and weeding out. Although the double hose regulator was gone, many of the techniques taught – like buddy breathing to share air with a single mouthpiece – were still based on double hosed regulators.

In 1966, however, this too began to change, though it would take almost 10 years for education to catch up with technology. In that year, John Cronin, a highly successful scuba manufacturer’s rep and instructor, and Ralph Erickson, a swimming coach and scuba diving instructor, formed a new training organization called PADI – the Professional Association of Diving Instructors. Seeking a new level of professionalism, Cronin and Erickson dedicated PADI to bringing mainstream education and business practices into scuba diving. Heading up the training side, Erickson put ink to paper and became the first person to apply formal instructional objectives to an international scuba diving program. At this time few noticed what this upstart little training organization was doing, but 15 years later, the little snowball Cronin and Erickson had started downhill would start an avalanche.

Scuba Diving Matures and Goes Mainstream Late 1970’s through Mid-1980’s

By the late 1970s, scuba diving as we know it today was in place. The first jacket-style BCDs came out in the mid-1970s, rapidly innovated upon and accepted so that by the mid-1980s the horse collar BCD was gone in most parts of the world. In 1983, the Orca Edge debuted, becoming the first widely accepted and used dive computer. Most of the dive community accepted the alternate air source (extra second stage) as the standard – or at least highly preferred – option for sharing air in an emergency. Durable and aesthetically pleasing silicone rubber began to replace perishable and ugly black neoprene rubber in masks and other gear.

Color options, as well as style and size, increased, with some manufacturers offering practically a rainbow by 1985. The equipment was just performing better, but looking better. Scuba diving wasn’t ugly any more. As the dive equipment continued to change, the changes in instruction introduced by Cronin and Erickson started radically shaping diving. Soon imitated by some competitive organizations, the PADI System of diver education abandoned the invalid, “learn-everything-there-is-to-know-about-diving” single courses with complex water drills that had no application when you really go diving. PADI’s approach followed modern instructional system design, breaking learning into steps and progressive courses. Professionally developed, fully integrated teaching systems with manuals, audiovisual, exams and other materials replaced arbitrarily chosen texts, boring lectures and made-up exams.

Training no longer emphasized weeks and weeks of pool drills, but instead shifted to focus on real-world scuba diving skills, transitioning faster to open water where you learned and practiced real scuba diving under instructor supervision. Learning to dive became more effective, more reliable and faster – and more fun.

The refinements in dive equipment coupled by the revolution in training rapidly altered the public perception of scuba diving. No longer a he-man, thump-your-chest sport, women and children began making up an increasing proportion of trainees, and more people under 20 and over 60 became divers. Mainstream media began to feature scuba diving directly and indirectly, and the message was the same: Diving is cool – try it.

The boom in participation fueled equipment development, as well as the growth and expansion of dive resorts from a handful to hundreds. Liveaboard diving entered the picture, giving divers more underwater time when they traveled. Self-contained and able to remain at sea for weeks at a time, these specialized vessels opened new, outlying dive destinations beyond the reach of shore-based dive operations.

Scuba Diving Matures and Gives Birth to Tec: Late 1980’s to Present

Since the diving boom in early 1980s, scuba diving has continued to grow and evolve. Equipment and technology advances continued. A prime example is the dive computer, which became more reliable, more compact and cheaper. Today, in most parts of the world it is more unusual to find someone diving without a computer than with one.

Since the diving boom in early 1980s, scuba diving has continued to grow and evolve. Equipment and technology advances continued. A prime example is the dive computer, which became more reliable, more compact and cheaper. Today, in most parts of the world it is more unusual to find someone diving without a computer than with one.

In 1988, PADI introduced the Recreational Dive Planner, the first dive tables developed exclusively for recreational, no stop scuba diving. The US Navy tables, in use by sport scuba divers since the 1950s, fell by the wayside. Today, the US Navy tables remain in widespread use by military and scientific divers, but seldom by recreational scuba divers. In 2005, PADI introduced the eRDP version and the world’s first electronic dive table.

Diver training has continued to evolve as well. The addition of videotape to instructional systems in the early 1990s made it possible for students to study basic knowledge development at home. Since then, DVDs, CD-ROMs and now web-based e-learning, have made course scheduling more convenient than ever. By eliminating the need for long lectures, these independent study tools allow today’s instructors to put more time into the personal needs of student divers.

In the early 1990s, propelled by the publication of aquaCorps, technical scuba diving emerged as a distinct new division of sport diving. With its roots in cave diving, tec diving appealed to the breed of diver that recreational scuba diving had left behind – the adventurer willing to accept more risk. Controversial at first, tec diving re-applied and innovated existing dive technologies to take divers beyond recreational limits. By 2000, the controversy had died down. Like it or not, tec diving was here to stay.

In the early 1990s, propelled by the publication of aquaCorps, technical scuba diving emerged as a distinct new division of sport diving. With its roots in cave diving, tec diving appealed to the breed of diver that recreational scuba diving had left behind – the adventurer willing to accept more risk. Controversial at first, tec diving re-applied and innovated existing dive technologies to take divers beyond recreational limits. By 2000, the controversy had died down. Like it or not, tec diving was here to stay.

At this writing, most of the general public sees scuba diving as a popular activity open to anyone who’s interested and who can meet the health requirements. The number of scuba divers continues to grow in virtually all parts of the world. Technical diving is also growing, albeit more slowly. It will likely remain a highly visible and influential minority in scuba diving community.

The Future of Scuba Diving

Looking back at the history of scuba diving, it’s natural to look ahead. How will technology and training change the way we dive? Will there be anything left to see underwater when we have the innovations of the mid-21st century? Tracing the past into tomorrow is a useful exercise for anticipating the future. But, the future isn’t set. As we steer our course into the future, we have our collective hands on the tiller, and we will alter course to accommodate influences and changes still unseen beyond the horizon. As we glimpse at how diving will be, remember that the picture is therefore necessarily inaccurate . . . and that’s probably a good thing.

Looking back at the history of scuba diving, it’s natural to look ahead. How will technology and training change the way we dive? Will there be anything left to see underwater when we have the innovations of the mid-21st century? Tracing the past into tomorrow is a useful exercise for anticipating the future. But, the future isn’t set. As we steer our course into the future, we have our collective hands on the tiller, and we will alter course to accommodate influences and changes still unseen beyond the horizon. As we glimpse at how diving will be, remember that the picture is therefore necessarily inaccurate . . . and that’s probably a good thing.

Recreational Scuba Diving

Based on current trends in scuba diving, computer technology, instructional system technology and the dive community, here are some reasonable predictions about what’s coming for recreational diving:

- Open circuit scuba will remain the primary mode of diving in the near future, but the use of CCRs (closed – circuit rebreathers) in recreational no-stop scuba diving will become common. Although some beginners will start with closed-circuit, which will not likely become common until CCRs are much more standardized in their configuration and operation, until support requirements they need become more widely available and until they become much less expensive.

- The electronic compass and other electronic navigation instrumentation will become a part of the dive computer.

- Heads up displays in scuba masks will not become common until technology makes them inexpensive and so compact that they do not substantially increase mask size and weight.

- Underwater voice communication will not likely be typical in open-circuit scuba diving, because the standard mouthpiece is simple and user-friendly, because of price, and because VOX (voice activated) transmission is more difficult to manage with open-circuit scuba due to noise. It will likely be common in CCR diving, because this level of diver is not as price sensitive, because this level diver is prepared for more equipment complexity, and because CCRs are quiet, which is ideal for VOX. Text messaging computer-to-computer, however, may become an option.

- EANx compatible computers and regulators will become standard because enriched air nitrox will be widely available. Manufacturers will stop producing air-only equipment completely.

- Generally speaking, dive equipment will continue to become more compact, lighter, streamlined and high-tech.

- Diver training is actually becoming increasingly diving intensive thanks to web-based learning. Instead of meeting for lectures, you can start a course at your convenience (time and place) online and complete the foundational knowledge development. You’ll then visit your dive center or resort to meet with your instructor and briefly review the material. Then, you move directly into putting it into practice through dive planning, dive preparation and diving.

Technical Diving.

Technical diving will change more than recreational diving in the immediate future. This is because it’s a younger sport and still maturing, and because tec divers are more technology-oriented and less price sensitive than the average mainstream diver.

CCRs will replace open-circuit scuba for many tec diving applications. You will have to be a certified recreational CCR diver to enter a tec diving course. CCR training and ergonomics will become enhanced through standardized basic control locations (e.g. oxygen bypass will be in the same place on all units), allowing motor skills to transfer more smoothly from one unit to another.

CCRs will replace open-circuit scuba for many tec diving applications. You will have to be a certified recreational CCR diver to enter a tec diving course. CCR training and ergonomics will become enhanced through standardized basic control locations (e.g. oxygen bypass will be in the same place on all units), allowing motor skills to transfer more smoothly from one unit to another.- Dives deeper than 90 metres (300 feet) will become routine.

- New decompression modeling methods will alter decompression methodologies radically.

- Voice communications will be standard in tec diving.

- The first sport hard suits will become available, taking tec divers as deep as 300 metres (1000 feet.) and even deeper

- Though tec divers will remain a small segment of the dive industry, the segment will grow. Liveaboard dive boats will offer more trips exclusively for tec divers and manufacturers will pay more attention to their needs.

- The line between recreational and technical diving will become more distinct as tec divers push the envelope with more sophisticated methods and equipment. However, tec innovations will continue to spill back into recreational scuba diving.

All 4 Diving Phuket – Samir Yasemov

Scuba diving Phuket